Introduction

As the winner of the World Plumbing Council Scholarship, I visited Hong Kong to investigate approaches to training and materials used for plumbing. The findings in this report[1] create a rich empirical backdrop for the story that unfolds. It discusses the risk to health from lead in the water on the service side – in domestic dwellings, schools, hospitals, colleges, universities and other public buildings. It is argued that declining standards in the training of plumbers in the UK over recent years and lack of regulatory governance have allowed for plumbing practices that are a serious risk to public health.

The World Plumbing Council Scholarship Visit to Hong Kong

The scholarship to Hong Kong was life changing for me, both as a researcher and a plumber. It was early in the visit when I learned about the risk to health from lead in the water. On the first meeting with academics and plumbing engineers, there was a water fountain at the venue, so I stooped to take a drink. I was halted by one of the locals who said “let the water run for about two and half minutes to allow any dissolved lead in the water to flush away”. I looked around at the modern infrastructure and building and asked what the problem was. The Hong Kong plumbing engineer, who had been assisting me, explained that Hong Kong had only started to use lead-free solder about ten years ago. The seriousness of the matter immediately became apparent and questions began to run through my mind:

What about the health risk to children?

What about the waste of water? (Including fuel energy used to clean water and treat waste)

My scholarship report (2017) stated that, in July of 2015, the Hong Kong Legislative Council found levels of lead in the Hong Kong water supply exceeding those stipulated by the World Health Organization. The Hong Kong Democratic Party (Legislative Council, 2016) said that more public housing estates had been sampled and more cases of lead had been found in the drinking water supply. An investigation took place with a Task Force, which was led by Dr H. F. Chan and included academics and other scientists. The Task Force was employed to conduct rigorous research and gather substantive evidence to link lead in the water supply to the solder used in copper plumbing fittings (Report of the Task Force, 2015). The Hong Kong government also set up an independent committee chaired by a judge.

The first thing that caught my attention about the Hong Kong case was that the lead poisoning was from copper pipes. In the UK, it seemed that warnings delivered to the public and plumbers about the risk of lead poisoning were predominantly associated with the risk to health from lead pipes. Indeed, the danger of lead poisoning from copper pipes, brass taps and fittings was not really something I had considered – and nor had most other plumbers I had spoken to.

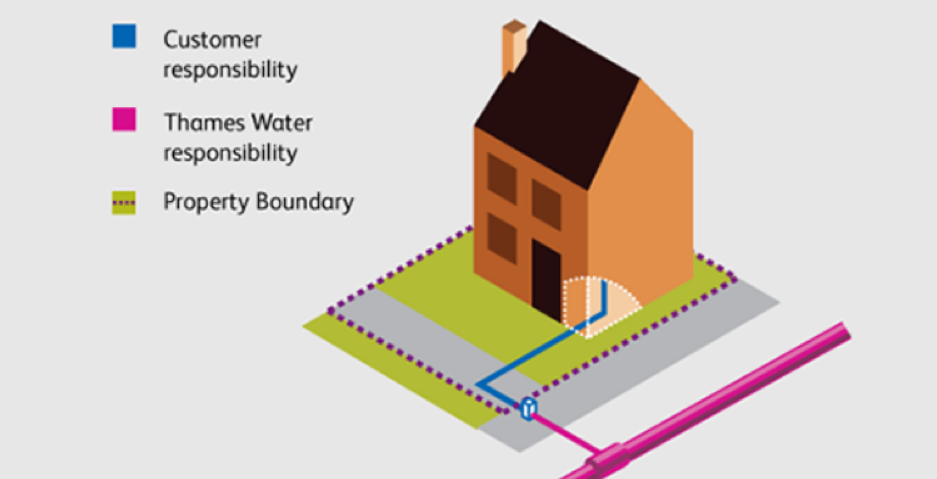

The second thing to gain my attention in Hong Kong was that the cases of lead-poisoning were occurring on the service side (blue in Fig.1) as opposed to the infrastructure side (pink in Fig.1), where cases of lead poisoning are often assumed to stem from.

Typical Water Layout in UK

Image: Thames Water

The Hong Kong water in the infrastructure was adequately dosed with phosphate and, when tested, showed miniscule levels of lead which were well within Chinese government regulations. At this point, it is also important to mention that there is no global standard for testing water for lead – the key issue that cannot be agreed in the Hong Kong case and internationally is the length of time the faucet is permitted to run before the ‘draw-off’ sample is taken for the test. For example – the USA only uses ‘first-draw water’, which is the very first measurement of water coming out of your pipes after sitting overnight. If the pipes are contaminated, that water will have the most accumulation of toxins. It seems most pragmatic to adopt the USA standard on an international level.

Despite the dosing of water in Hong Kong, high levels of lead in the water were found on the service side in some copper pipe systems, which were jointed with lead solder. However, it is unknown how widespread the problem may be because the lead in the water problem was often found to be caused by poor workmanship.

The Hong Kong Task Force (2015:16) reported that ‘Solder materials seeped into the pipe due to poor workmanship by overheating for an extended period of time and/or applying excessive solder’ (see Fig.2).

Fig. 2 End feed soldering and poor workmanship explained

The joint with excess solder running down the inside of the pipe is due to the incompetence of the installer and, consequently, may result in high levels of lead in water, such as those reported in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong report revealed that there was a shortage of licensed plumbers and that although the water regulations stated that licensed plumbers should be doing the work, they were mainly operating in a supervisory capacity. Hence, there was a discrepancy between what should be done and what was actually happening in practice. Dr Raymond HO Chung-tai stated that a Licensed Plumber is not a Plumbing Worker in large-scale projects (HO Chung-tai, 2016:1). Instead, Licenced Plumbers are supervisors or engineers overseeing the projects. The Construction Industry Council in Hong Kong suggested that legislative requirements should be revised to comply with actual needs on the ground – with properly-trained and authorised plumbing workers, who have been assessed to ensure that their skills meet the contract’s requirements.

The problems with phosphate water treatment

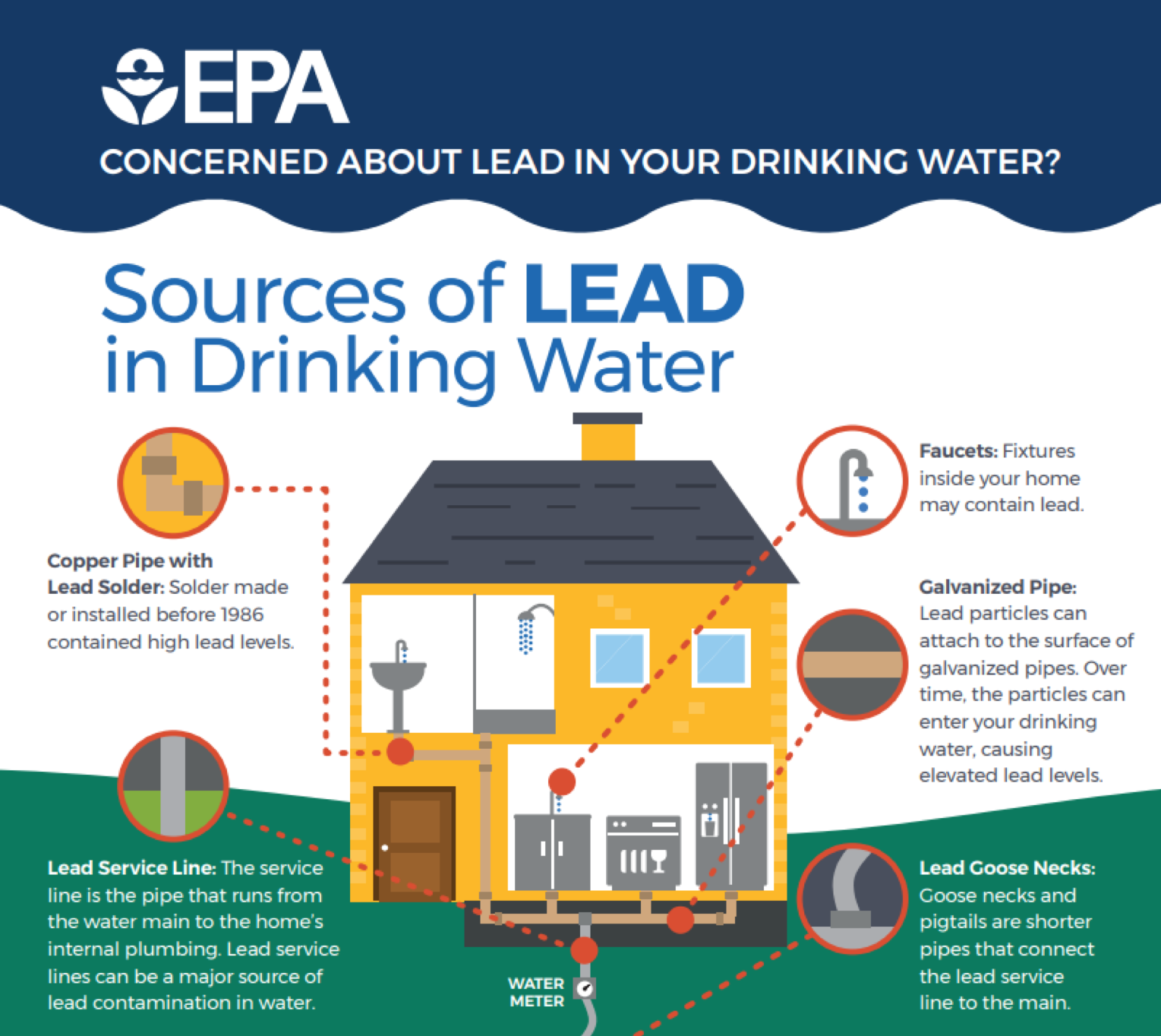

The Hong Kong study led me to believe that the same bad workmanship on copper jointing may be true for some English ‘legacy plumbing’ systems. The UK Water Research Centre (in Potter, 1997) highlighted the possibility that, owing to galvanic action between copper and lead solder combinations, copper pipework may actually result in higher concentrations of lead in drinking water than lead pipes alone. Galvanic action or bimetallic corrosion is an electrochemical process causing one metal to corrode preferentially when it is in contact with another in the presence of an electrolyte (tap water). Indeed, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (2018:1) states:

Lead can enter drinking water when service pipes that contain lead corrode, especially where the water has high acidity or low mineral content that corrodes pipes and fixtures. The most common problem is with brass or chrome-plated brass faucets and fixtures with lead solder, from which significant amounts of lead can enter into the water, especially hot water. Homes built before 1986 are more likely to have lead pipes, fixtures and solder.

Dr Oliphant (cited in BBC, 2000) at the Water Research Centre considered leaded solder combined with copper pipes to be potentially more dangerous than lead pipes on their own. However, in the UK, many supplies are treated with phosphate to reduce plumbo-solvency, but this is not a sustainable solution and any benefits would stop if this treatment was suspended or removed (Reddy, 2018a).

However, despite the water in Hong Kong being phosphate treated, high levels of lead were found where poor workmanship was involved. In a sense, the UK and USA face the same risk from legacy plumbing because the extent of poor workmanship is unknown. Cleary’s (2018) compelling account of the Flint Michigan lead in the water scandal leads us to question whether we should put our complete faith in water treatment. In a cost saving-move, Flint City switched from purchasing water from the Detroit Water System, to using water from the Flint River. This occurred in April of 2014 and would eventually lead to one of the most severe public health disasters in modern history. Cleary (2018) stated that every branch of government failed in its responsibility – Local, State, and Federally elected and appointed officials failed to protect the public. He went on to argue that their employees also share in the blame for this completely preventable situation. The lack of social responsibility is reflected in the case of the Director of the Flint Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program. Higher-than-usual levels of lead were found in Flint’s children during the summer of 2014, but the report was buried and never forwarded to health officials (Cleary, 2018).

Fig.3 Flint Lead in the water incident

Flint had certainly raised public awareness about the risk of lead in the water. Nevertheless, the United States of America does not have a strategy for dealing with the risk of lead poisoning from legacy plumbing on the service or user side. This risk is arguably not yet widely understood in the USA, but there have been some positive events in regard to lead in the water. The United States ‘Safe Drinking Water Act’ was introduced under former President Barack Obama in 2014, which led to the US Congress revising the definition of ‘lead-free’; stipulating that all pipes, pipe fittings, plumbing fittings and fixtures in contact with wetted surfaces must meet a 0.25% weighted average lead content and 0.2% for solder and flux (United States Environmental Agency, 2018). The United States Environmental Agency (2018) provides explicit warnings to the public about the dangers of lead in water from legacy plumbing.

Fig. 4 United States Environmental Protection Agency – Public Information on Legacy Plumbing

The UK situation on lead in the water

When we consider the situation in the UK (and possibly the rest of Europe), a different approach is taken to address the lead in the water risk. In the UK, it is assumed that the drinking water is not plumbosolvent because not all waters are corrosive. Instead, it is argued by the water authorities that treatment is likely to eliminate the prescribed risk or reduce it to a minimum level.

However, the UK may have a more significant problem than most other developed Western nations because it is one of the few countries that still use metals, such as copper, for the majority of drinking-water plumbing work. The ratio given by plastics expert Tsalic (2017) at the ‘Plastic Pipes Inside Buildings’ international conference in Cologne, Germany, was 70% metals to 30% plastics for the UK, and 30% metals to 70% plastics in other developed Western nations. The market for plastic plumbing in the West is growing, while countries such as China, Australia and India already have lead-free plumbing systems made of environmentally-friendly plastics, which recycle at much lower temperatures compared to metals.

In the UK, the Water Regulation Advisory Scheme (WRAS) is the minimum quality standard for plumbing materials. WRAS (2018) approvals require testing of all non-metallic materials in contact with drinking water based on BS 6920, however…

…there are no UK regulatory criteria for metallics in contact with drinking water.

The USA has a 0.25% weighted average lead content and the UK has no regulations – begging the question of how much lead is in UK plumbing fittings and components such as brass alloy water sections on hot water heaters and brass taps and fittings bought at DIY outlets. In this context, there are no checks for lead content in the UK.

Training culture and stigma with plastic plumbing in the UK

My own PhD research revealed that City and Guilds plumbing qualifications at level 2 are mainly theory, with the practical sessions involving lots of hand-threading and jointing of low-carbon steel pipe – this, despite fewer than 10% of plumbers operating in the UK ever needing to use this skill. Moreover, the current plumbing qualifications contain hardly any technical training on high-tech plastic and multi-layer pipes for cold/hot water and heating – when plastics are used in colleges, it is usually because the fittings can be re-used continuously to save money. UK plumbers are very much acculturated into the use of metal plumbing through apprenticeships and ‘copper is king’ & ‘brass is class’ values which have become associated with quality. In contrast, plastic pipes are often installed in a poor way and get negative publicity from many professional plumbers:

Fig 5. Poor quality stigma with plastic plumbing in UK

Image: Plumbing apprentice Luke Veacock

Another culture reported is the use of lead solder for training purposes in colleges because it is much cheaper than lead-free solder. Not only do UK colleges often breach the water regulations, they arguably increase the risk of mistakes by ‘unapprenticed’ or partially-trained plumbing students who use the short courses as a launch-pad into self-employment as legitimate plumbers. It could be argued that these students may be more inclined to use lead solder on potable supplies because they have only learned plumbing in a college and often work unsupervised as self-employed plumbers. In the UK, there is no licence to practice for plumbing, so anyone can call themselves a plumber and open up a business. In my home town of Torquay, England, a kitchen fitter pleaded guilty for using lead solder illegally in the fitting of B&Q kitchens – he was subsequently prosecuted (South West Water, 2018). A different case handled by Severn Trent Water Ltd, England, (Drinking Water Inspectorate, 2017) carried a significant risk classification. Lead solder (which is illegal) was discovered through the plumbing system of the property. The Local Authority is conducting a formal investigation into the contractor who worked on the plumbing system at the premises.

With the rise of short plumbing courses and competent persons schemes over the past two decades, plumbing standards have declined. My PhD research argued that it was hazardous for full-time college students to graduate and progress into self-employment unsupervised because the college-based training and assessment were incapable of replicating the reality of the workplace. Therefore, full-time plumbing students are ill-prepared and may face a reality shock because the skills required in the real context of work are different from those learned in college. In my study, tutors were unanimous in their judgements about college-based training and assessments that fail to adequately represent the reality, problems and experiences of plumbers operating in the workplace:

“College exercises in the workshop are not real-life exercises; they are simulated. Everything is nice and level and flat. There are no problems, it’s all there. It’s like I said, when you get into the real world and you get into someone’s house, it’s completely different.” (Tutor Darrel College 3, cited in Reddy, 2014: 156.)

Many tutors expressed their concern for college-based preparatory courses and qualifications because students did not acquire the necessary work experience to become competent. An on-site assessor in my study told of how he had to terminate a workplace assessment because the inexperienced students failed to locate the isolation for the mains water supply for the job. The assessor described locating the position of the mains stop-tap on the pavement outside as basic knowledge for practising plumbers. However, the full-timers who were being assessed had not experienced this other than in books and simulations in college, where the mains water isolation was always easy to locate and isolate (Reddy, 2014).

My (Reddy, 2014; 2017; 2018b; 2018c) findings on the quality of Further Education training and assessment in England supports the position of the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR, 2017b), which said FE provision had been shaped by the government rather than employers. IPPR argued that much of the current provision was delivered at a low level, with shallow curriculums, low rates of progression and low labour market returns. IPPR were scathing about college provision, stating that “the FE sector is often failing to give learners the skills and experience that they need to progress into a sustainable career in the industry, and it is failing to meet the needs of employers” (IPPR , 2017a: 16). On the issue of quality, IPPR (2017b: 70-71) stressed that “comparatively few teachers in the sector are from an industry background, and many do not have teaching qualifications”.

While many of my findings in relation to the inadequacy of competency assessments support the existing literature on vocational education and training, my research brings about new insights in relation to health and safety. My study reinforces growing concerns from the Gas Industry Safety Group (GISG) and the Institution of Gas Engineers and Managers (IGEM) (2016), who reported an increase in unsafe gas work by recently qualified engineers – from 1% to 5% (Gas Safe Register, in GISG/IGEM, 2016:1). They highlighted an over-emphasis on classroom theory and a dependency on online multiple-choice tests, with gas safety exams being sat by novices who “were allowed to keep re-sitting the tests until they passed” GISG/IGEM, 2016:20). These findings build on the earlier work of the Unite Union (Unite 2012:10), which stated that college-based courses can create “under-qualified individuals, who have the misconception that they are then able to undertake safety-critical work”. I attended a parliamentary hearing to give evidence as part of the Gas Engineer Training Standards Inquiry (GETSI, 2018). It was conducted by the All Party Parliamentary Carbon Monoxide Group (APPCOG), which commissioned Policy Connect to conduct the research. The inquiry is a response to a significant rise in reports of poor quality training of Gas Safe Registered Engineers.

Therefore, a licence to practice in the UK does not necessarily determine quality work or a reduction in unsafe work. For this reason, there needs to be a call for a licence to practice in plumbing that is accompanied with a better understanding of assessment science and competence.

Conclusion

To conclude, this short paper attempted to bring together the key issues for debate and action over coming months in both the USA and UK.

On the basis of the discussion, the following actions could be recommended:

- Policies: A policy for all new housing to be ‘certified’ by professional plumbers as having lead-free plumbing. Dangerous legacy plumbing should be removed from existing housing stock – in turn, improving public health and creating jobs.

- Standards: Immediate improvement of international standards for checking drinking water and plumbing products. Specifically, a global standard to test for lead in water and 0.25% maximum permitted lead in alloys in contact with drinking water.

- Research: Studies on the long-term effectiveness and environmental impact of phosphate treatment on decaying plumbing infrastructure versus replacement.

- Training: There needs to be an awareness of the danger of water supply contamination – especially from lead. This can only occur if trainees are shown the risks.

Indeed, relating to the latter point, my next paper with IAPMO will draw on my CMALT research in digital pedagogy to explain the training and assessment system required to bring quality to the plumbing industry in the UK and the USA.

About the Author |

|

|

I am a master plumber and fellow of the Chartered Institute of Plumbing and Heating Engineering in the United Kingdom. I have worked self-employed on the tools for over thirty years. During this time, my domestic plumbing firm trained local young people as apprentices and my company helped military veterans resettle to civilian life through training and employment in the plumbing industry. My evenings were often spent training plumbers in the local college and, in more recent years, I have been involved with research in the field of Education. In 2014, I completed a PhD, which investigated tutors’ and students’ perceptions and experiences of full-time college courses and apprenticeships in plumbing, allowing me to identify the problems with English plumbing training. My post-doctoral employment included teaching plumbing in Further Education and Environmental Science at the University of Plymouth. My independent research work included developing a digital means of teaching, learning and assessment that makes use of closed social media groups. I was awarded Certified Member of the Association of Learning Technology (CMALT) in 2017 for my research portfolio on digital pedagogy – I am currently in the early development stage of an independent training platform, known as ‘ApprenticeshipMovement’, which aims to use digital technologies for on-site assessments. My theory of ‘Emergent Apprenticeships’ underpins this new approach to training, and I have presented it at the Universities of Cambridge and Oxford, as well as at Hong Kong Polytechnic University. I am also the plumbing expert for the UK’s Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual). My industrial and academic roles support my public health awareness position as CEO of leadinthewater.com – I am a regular speaker at international conferences concerned with both industrial and academic topics. |

BBC (2000) ‘Scotland’s Poison on Tap’, Frontline, Tue 9th May, [Online], Available, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/739003.stm [6 Feb 2017].

Cleary, S. (2018) ‘Flint Can Flint Michigan Happen Here? – Understanding Our Water System’, [Online], Available, https://www.dropbox.com/s/dnrfxkvcg61sn5h/2018-02-14%2015.00%20The%20Flint%20Michigan%20Water%20Crisis_%20%20What%20Went%20Wrong%20and%20Can%20it%20Happen%20Again.wmv?dl=0 [20 Sep 2018].

Drinking Water Inspectorate (2017) ‘Annual report’, [Online], Available, http://www.dwi.gov.uk/about/annual-report/2017/significant_events.pdf [10 Sep 2018].

Gas Engineer Training Standards Inquiry (2018) ‘All Party Carbon Monoxide Group’, [Online], Available, http://www.policyconnect.org.uk/appcog/news/getsi-gets-going [April 17 2018).

Gas Industry Safety Group and Institution of Gas Engineers and Managers (2016) ‘Gas Engineer Training Report’, [Online], Available, http://www.gisg.org.uk/Publications/GISG_IGEM_Gas%20Engineer%20Training%20Research%20Report.pdf [20 Feb 2017].

HO Chung-tai, R. (2016) ‘Congratulations to Plumbing Engineers in Hong Kong’ link no longer available [last accessed 18 Nov 2016].

Institute for Public Policy Research (2017a) ‘Another lost decade? Building a skills system for the economy of the 2030s’,[Online], Available, http://www.ippr.org/publications/skills-2030-another-lost-decade [14 March 2018].

Institute for Public Policy Research (2017b) ‘Building Britain’s Future’, [Online], Available, http://www.ippr.org/publications/building-britains-future [17 April 2018].

Legislative Council (2016) ‘Special House Committee meeting on 11 July 2016: Updated background brief on lead in drinking water incidents’, [Online], Available, http://www.legco.gov.hk/yr15-16/english/hc/papers/hc20160711cb2-1866-2-e.pdf [3 Nov 2016].

Potter, S. (1997) ‘Lead in Drinking Water’, Research Paper 97/65, Science and Environmental Section, House of Commons Library, [Online], Available, https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/RP97-65 [6 Feb 2017].

Reddy, S. (2014) ‘A study of tutors’ and students’ perceptions and experiences of full-time college courses and apprenticeships in plumbing(link is external)’, University of Exeter PhD thesis, [Online], Available, https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10871/15728 [10 Nov 2016].

Reddy, S. (2017) ‘World Plumbing Council Scholarship Report: A comparative education study of plumbing and training: Hong Kong and England’, World Plumbing Council [Online], Available, http://worldplumbing.org/assets/uploads/2016/11/2015-WPC-education-and-training-scholarship-report-Simon-Reddy.pdf [30 Jan 2018].

Reddy, S. (2018a) ‘Exploring the Risks of Lead from Legacy Plumbing’, Watersafe, [Online], Available, https://www.watersafe.org.uk/blog/posts/risks-of-lead-legacy-plumbing/ [20 Sep 2018].

Reddy, S. (2018b) ‘The problem with Further Education and Apprenticeship qualifications’, FE News [Online], Available, https://www.fenews.co.uk/featured-article/16032-the-problem-with-further-education-and-apprenticeship-qualifications [23 March 2018].

Reddy, S. (2018c) ‘Opinion: Dr Simon Reddy on employability and quality in Further Education’, [Online], Available, https://ec.europa.eu/epale/en/blog/opinion-dr-simon-reddy-employability-and-quality-further-education [20 Sep 2018].

Report of the Task Force (2015) ‘On investigation of excessive lead content in drinking water’, Hong Kong Government, [Online], Available, http://www.devb.gov.hk/filemanager/en/Content_3/TF_Final_Report.pdf [8 Nov 2016].

South West Water (2018) ‘Kitchen fitter fined for use of lead solder’, [Online], Available, https://www.southwestwater.co.uk/about-us/latest-news/news-2018/kitchen-fitter-fined-for-illegal-use-of-lead-solder-on-water-pipe/ [6 Aug 2018].

Thames Water – ‘Image of house and service pipes’ [Online], Available, https://www.thameswater.co.uk/Help-and-Advice/Water-Quality/Whats-in-your-water/Lead/Lead-in-your-environment [6 Aug 2018].

Tsalic, N. (2017) ‘Plastic Pipes Inside Buildings’ conference, [Online], Available, https://www.plastic-pipes.events/previous-edition-2017/ [20 Sep 2018].

Unite (2012) ‘Unite the Union response to the Department for Business, Innovation & Skills and Department for Education – Richard Review of Apprenticeships, Executive summary’, [Online], Available, http://centrallobby.politicshome.com/fileadmin/epolitix/stakeholders/stakeholder s/Unite_the_Union_response_to_the_Richard_Review_of_Apprenticeships_201 2__4_.pdf [2 Nov 2012].

United States Environmental Protection Agency (2018) ‘Basic information about lead in drinking water’, [Online], Available, https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/basic-information-about-lead-drinking-water#getinto [20 Sep 2018].

Water Regulations Advisory Scheme (2018) BS6920:2014 [Online], Available, https://www.wras.co.uk/consumers/resources/glossary/bs6920/ [20 Sep 2018].

[1] http://worldplumbing.org/assets/uploads/2016/11/2015-WPC-education-and-training-scholarship-report-Simon-Reddy.pdf

24 Sep 2018

24 Sep 2018

Posted by BP Journal

Posted by BP Journal